Houston County is growing. That much is clear. What is less clear is whether that growth is making life better, or simply more expensive and more spread out. The real question isn’t whether Houston County grows, but whether that growth produces long-term prosperity – or long-term obligations.

New subdivisions and apartments continue to appear on the edges of our developed areas.

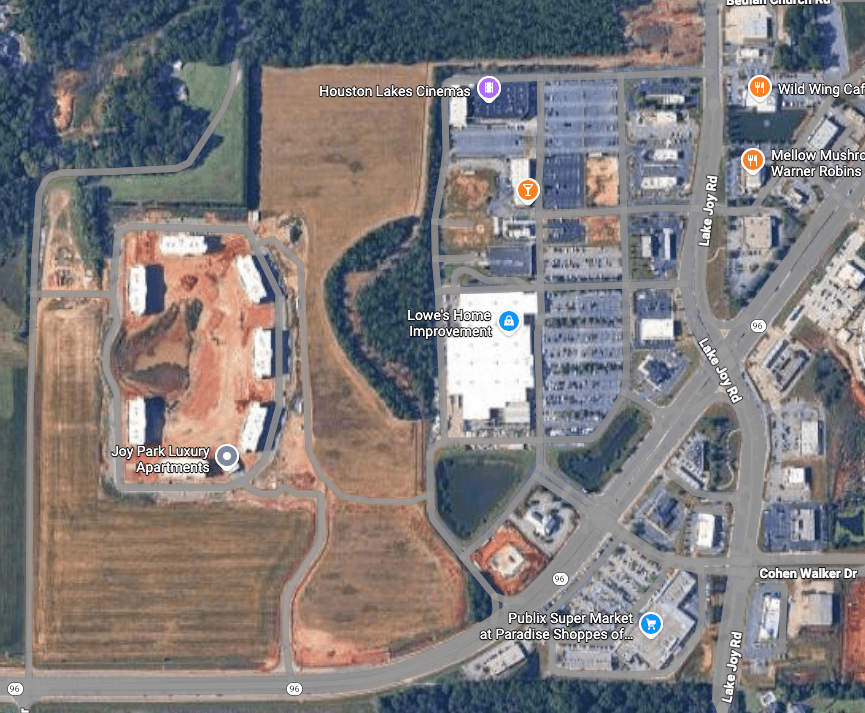

Meanwhile, inside our cities – Perry and Warner Robins, especially – many older commercial corridors, shopping centers, and vacant parcels remain underused or stagnant. Traffic increases, infrastructure costs rise, and local governments face growing pressure to extend roads, utilities, and services farther outward.

This often leads to a familiar refrain: we need to stop “the growth”.

But what if the real issue isn’t growth itself, but the incentives that quietly determine where growth goes?

To explore that question, it helps to revisit an old idea with renewed relevance: Georgism. In plain terms, it’s the idea that we should tax land value more than buildings, because land value is created by the community, while buildings are created by the owner.

The Growth Pattern We Didn’t Intend – But Did Incentivize

Houston County’s development pattern didn’t emerge by accident. Like much of Georgia, it took shape during the post–World War II era, when highways, automobiles, and low-cost greenfield development defined success.

New homes were easier to build on open land than within existing cities. Over time, outward expansion became self-reinforcing. Zoning, parking requirements, and infrastructure policies all evolved to support that pattern.

Today, the consequences are familiar:

- We want less traffic, yet growth spreads farther out.

- We want lower taxes, yet infrastructure costs keep rising.

- We want to protect neighborhoods, yet reinvestment stalls along older corridors.

- We say we oppose low-productivity growth, yet our rules continue to incentivize it.

These outcomes are frustrating because they persist even when communities actively try to manage or slow growth.

To understand why, it helps to look beyond zoning and transportation and examine how land itself is taxed.

Why Georgism Still Matters

Georgism is named after Henry George, a 19th-century American economist writing during a period of rapid urbanization, land speculation, and widening inequality.

George made a simple observation: land becomes valuable not because of what an individual owner does, but because of what happens around it – population growth, public investment, nearby businesses, roads, schools, utilities, and services.

Yet, traditional property taxes often do the opposite of what communities intend:

- They penalize improvements – buildings, renovations, and reinvestment.

- They make it relatively cheap to hold valuable land idle.

George’s proposed solution was not regulation or land redistribution, but incentive alignment: tax land value more heavily, and tax buildings and improvements less, or not at all.

Georgism isn’t anti-growth. It’s anti-speculation and anti-waste. It asks a simple question:

If land is valuable because of the community, should holding it idle be rewarded?

This doesn’t tell anyone what to build. It simply stops rewarding the choice to hold high-value land idle while the public carries the long-term costs.

Why Georgism Faded – and Why Georgia Never Adopted It

If Georgism seems logical, why didn’t it become the norm?

Nationally, it ran into three forces.

First, politics. A system that raises the cost of holding valuable land idle directly threatens land speculation. Those interests tend to be concentrated, organized, and influential.

Second, zoning replaced tax reform as the main growth-management tool. Cities regulated land use rather than rethinking land incentives. Over time, this produced rigid separation of uses, parking mandates, and long approval processes—often freezing existing patterns in place.

Third, timing. Georgia’s major growth surge occurred after Georgism had already faded from national prominence. By the time communities like Warner Robins and Perry were expanding rapidly, conventional property taxation and suburban development models were firmly entrenched.

Georgia’s local governments also operate under constrained taxing authority. Fundamental changes to property taxation require state authorization. In other words, cities and counties can’t just adopt a new tax structure on their own. Unlike some states, Georgia never opened a broad pathway for land-value-based experimentation.

The Incentive Problem in Houston County Today

Under Georgia’s conventional property tax system, land and improvements are taxed together. That creates two quiet but powerful incentives:

- Improving property can raise your tax bill.

- Holding underused land is relatively cheap.

This matters more than it seems.

In Houston County today:

- Raw or lightly improved land at the edge is cheap to hold.

- Infrastructure costs are effectively socialized – roads, utilities, and long-term maintenance are paid collectively.

- The tax system does not penalize low productivity per acre.

This isn’t “socialism” as a political label – it’s simply the financial reality that long-term costs are shared publicly while land gains accrue privately. That structure quietly favors outward expansion over reinvestment where infrastructure already exists.

As a result, it is often safer to:

- keep a vacant lot empty,

- maintain a surface parking lot,

- leave an aging strip center underused,

than to redevelop those properties into something more productive.

Meanwhile, greenfield development looks clean and straightforward: open land, fewer constraints, easier layouts, and fewer retrofit challenges.

Financially fragile growth isn’t a cultural preference. It’s an incentive outcome.

Most people can picture the pattern. An aging shopping center with an oversized parking lot sits half-used for years, while new subdivisions and new commercial pads pop up farther out. Then come the follow-on demands: widen the road, add turn lanes, extend utilities, build more capacity. The land we’ve already served with infrastructure stays underused, while we build new infrastructure to chase the next edge.

This pattern isn’t inevitable – it’s what we get when reinvestment is penalized, and outward expansion is the easiest path.

The “Stop the Growth” Paradox

Many residents who oppose outward expansion understandably support policies they believe will stop growth:

- large-lot zoning,

- strict separation of uses,

- down zoning,

- height limits,

- heavy parking requirements,

- lengthy approval processes.

These tools feel protective. They promise stability.

But they don’t eliminate demand. They redirect it.

When infill becomes difficult or risky, growth moves to where it is easier, often just outside city limits. The result is growth that adds lane-miles and pipe-miles faster than it adds a durable tax base.

Ironically, many of the policies used to “stop growth” end up accelerating the very pattern people oppose.

This isn’t hypocrisy. It’s an unintended consequence of incentive blindness.

What This Means for Perry and Warner Robins

Perry and Warner Robins both have significant public investment already in place – roads, utilities, services – and substantial areas of underused land.

In Perry, the challenge is whether growth strengthens the city’s core or bypasses it. When reinvestment is hard and greenfield development is easy, the market naturally skips inward opportunities.

In Warner Robins, corridors like Commercial Circle, Green Street, or North Davis Drive represent sunk public investment. Under a land-value-forward lens, underused parcels along these corridors would face pressure to become more productive or change hands.

This is not about forcing density. It’s about ensuring that valuable land does not remain locked into low return uses indefinitely while the public obligations keep expanding outward.

Centerville and the other fast-growing communities outside city centers – Kathleen, Bonaire, and Elko – sit in the crosscurrent, close enough to feel growth pressures, small enough to feel every mistake. Incentives that favor reinvestment first can help preserve both fiscal health and community character.

Farms, Rural Land, and a Houston County Reality Check

Any discussion of land value immediately raises a fair question: what about farmers?

In Houston County, that question matters. Agriculture is not an abstraction here. The county’s political and cultural history — including prominent agricultural leaders — demands that rural land be taken seriously.

The good news is that Georgia already does this.

Georgia law already distinguishes productive land from speculative land through tools like Conservation Use Valuation Assessment (CUVA). Land in active agricultural or forestry use is assessed based on its current use, not speculative development value. That distinction exists because lawmakers recognized long ago that productive land should not be taxed into premature conversion.

County tax assessors already classify land by use, separate land from improvements for valuation purposes, and rely on GIS, aerial imagery, and periodic review. Identifying actively farmed land versus idle or speculative land is routine, not theoretical.

A land-value-forward approach does not target working farms. It targets land held idle in high-demand locations, especially near infrastructure and growth corridors.

In fact, reducing speculative edge-growth pressure often benefits farmers by slowing price inflation and preserving viable agricultural landscapes longer.

This is not an anti-rural policy. It is pro-productivity.

County-Wide or City-Only?

If Georgia ever allowed land-value-based taxation, the strongest framework for Houston County would be county-wide but calibrated to infrastructure and service context.

Land markets operate regionally. If incentives change only inside city limits, some pressure simply leaks outward.

A county-wide framework avoids that problem while still recognizing reality: land served by roads, utilities, and services carries different public costs than land that is not.

The principle is simple:

The greatest pressure should exist where public investment already exists, and no area should function as a free holding zone for speculation.

Anticipating the Objections

Is this just a way to force density?

No. It changes incentives, not mandates outcomes.

Won’t landlords pass the tax to renters?

Rent is constrained by market demand. Vacant and underused land cannot pass on costs if it produces nothing. That pressure is the point.

Isn’t this too complicated?

Georgia already runs complex land classifications, exemptions, and use-based assessments. The administrative tools exist.

Won’t this hurt farmers?

Georgia already protects productive land through CUVA and similar programs. A land-value lens aligns with that logic rather than contradicting it.

Don’t we need growth to fund services?

Yes, but growth that spreads outward faster than it produces value often weakens long-term fiscal stability. The pattern matters.

Is this “left” or “right”?

Georgism doesn’t fit neatly into the left / right dichotomy. It’s pro-market in the sense that it rewards productive use and discourages land speculation, while also recognizing that land value is created by public investment and community growth.

Won’t this punish seniors on fixed incomes?

Any real reform would need protections such as circuit-breakers or deferrals for cash-poor, asset-rich households — especially seniors — so the goal remains for better land use, not displacement.

Isn’t land value hard to measure?

Assessors already estimate land value separately from buildings as part of routine appraisal practice; the debate is less about whether it can be measured and more about what we do with that information.

Not a Proposal – A Better Question

This is not a call to adopt a new tax tomorrow. It is an invitation to think more clearly about cause and effect. Georgia doesn’t currently authorize true split-rate land taxation at the local level, so this is primarily a lens for understanding incentives, and for improving the tools we can use today.

Houston County must accommodate the growth the base needs. One could argue that it’s our patriotic duty. Our growth mindset is well established. Still, we desire to conserve our familial way of life, our rural lands, and agricultural fabric. To control outward expansion, lower long-term costs, and achieve healthier cities, the conversation cannot stop with zoning and traffic. It must include the incentives that shape land use in the first place.

Georgism offers a useful lens, not because it is radical, but because it asks an old, practical question:

Are we rewarding productivity or speculation?

That question is worth asking before the next mile of road is built, and the next opportunity is missed.

One Thing We Can Do Today

Georgia law doesn’t allow cities and counties to adopt a land-value tax tomorrow. But local governments are not powerless.

There is one thing Houston County and its cities can do right now:

Stop making reinvestment harder than greenfield development.

Today, it is often faster, cheaper, and less risky to build on the edge than to reuse land we already serve with roads, utilities, and services. That is not a law of nature — it’s a product of local rules, processes, and priorities.

Changing that doesn’t require a new tax authority. It requires:

- zoning that allows incremental reuse by right,

- parking rules that reflect actual demand,

- approval processes that reward reuse rather than punish it,

- and infrastructure decisions that prioritize existing places before expanding outward.

None of these force density. None dictate outcomes. They simply remove barriers that currently tilt the market toward financially fragile growth.

Georgism doesn’t tell us exactly what to do next. It helps us see why this is the place to start.

And once reinvestment becomes the easiest path — not the hardest — Houston County’s growth story begins to change for the better.

Leave a comment